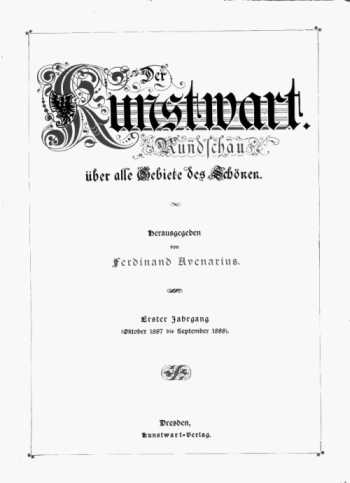

Der Kunstwart

München, 1.1887 – 50.1936/37

Rundschau über alle Gebiete des Schönen; Monatshefte für Kunst, Literatur und Leben

(from 26. 1912/13 changing titles)

(Culture – Literature – Politics ; 20)

53,514 pages on 646 microfiches,

2006, ISBN 3-89131-468-X

Diazo negative: EUR 3,500.–

(excl. VAT)

Silver negative: EUR 4,200.–

(excl. VAT)

»At that time the Kunstwart was an intellectual force in Germany«. This was the recollection of Theodor Heuß, the first President of the Federal Republic of Germany, of the journal for which he had worked as a young reviewer »back then« – between the Fin de siècle and the First World War.

This fortnightly cultural journal first saw the light of day in Dresden, then a centre of the emerging »Lebensreform« (Life-reform) Movement, in 1887. This movement wished to coerce the industrial alienated environment into providing possibilities for a natural and at the same time aesthetical human existence. In this holistic spirit Kunstwart founder Ferdinand Avenarius, a nephew of Richard Wagner, reached out towards a growing middle class that was non-academic but hungry for education. He regarded it as a moral aesthetic education of the people to offer them a »review of all aspects of the beautiful«. And so his journal not only covered literature, art, music, theatre and the still young photography but explicitly also useful crafts from bookbinding over ladies hats and tablecloths to brick kilns. As a principle for product design it advocated the harmony of material and purpose, for the visual arts a national romantic conservatism a »real German« aesthetic – to which a mixture of realism and mystical inwardness applied as in the paintings of Dürer, C.D. Friedrich or Böcklin.

Avenarius managed to raise the somewhat scanty distribution by changing to the Callwey Publishing House in Munich in 1894. At the succeeding high point of the curve of success – with an edition of over 20000 – the Kunstwart was able to underline its postulates with illustrative material. Starting in 1898 the journal contained art reproductions and sheet music. In order to connect the readers and supporters institutionally Avenarius founded the Dürer Union in 1902. This was a sounding chamber for the marketing of so-called Kunstwart-Enterprises – books, calendars, and picture portfolios – however, above all it conducted cultural work through political input, artistic commissions and it own press service. The »Kunstwart Spirit« was soon proverbial and Theodor Heuß attested its taste forming influence: »One could see (…) on the wall decorations, the choice of furniture, in front of the bookcase if a recipient of Kunstwart lived here. Nothing comparable had existed in Germany either before or afterwards«. The journal directed its readers not only in question of taste but also informed them about the market power of their own purchasing behaviour – if necessary through deterrence. An illustration of »house-horrors« displayed various knick-knack products of the year 1908 including a mouth organ in the form of a goldfish.

The high point of its success was already passed as in a phase of political radicalisation during the war, from 1915 to 1919, the journal appeared under the title »Deutsche Wille« (The German Will). Avenarius’ successor Wolfgang Schumann was also not able to stop the decline in readers. His openness towards the left overtaxed the editorial staff and his intellectualism overtaxed the readership. From 1921 the Kunstwart only appeared monthly, from 1934 bimonthly, by which time it was already called the »Deutsche Zeitshrift«. Its fiftieth anniversary in 1937 was also its final year.

Culture and politics, the history of institutions and way of life: many facets of this unique journal contribute to its value as a resource. Franz Kafka read it and both Hermann Bahr and Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote for it and in 1912 the publicist Moritz Goldstein started an argument in its pages between Jewish intellectuals over Zionism contra German patriotism the »Kunstwart Debate«. The Kunstwart itself was not presented as a work of art unlike »Pan« and or the »Jugend«. With a reasonably priced presentation it pursued the quasi anti-elitist aim of greatest possible reach. In this it also shows that it not only recorded the daily, social and aesthetical historical processes of its times but was also a product of their interactions within the »Lebensreform« a movement with a fascinatingly wide agenda. A vital tradition for many patterns of thought, then as now, strongly present in Germany such as the environmental movement, nudism and the supporters of health food or quality workshop products. For fifty politically and culturally turbulent years the Kunstwart evaluated all areas of aesthetics with a multiplicity of joyous opinions, which emphasised its stated aims. It also stands, no less, for the history of fifty years of German conservative ideology: From Wilhelminian pride of the delayed nation through the conservative revolution of the Weimar Republic up to the internal emigration of the Nazi period.