The Music Prints from the Augsburg State and City Library 1488 – 1630

438 prints with 105,000 pages

Schletterer-Catalog publ. 1878

Online

2010, ISBN 978-3-89131-518-7

Purchase: EUR 9,240.–*

Annual License: EUR 924.–*

Access to Online Edition

Microfiche Edition

1,445 microfiches, 2000, ISBN 3-89131-241-5

Silver negative: EUR 9,240.–*

Catalogue

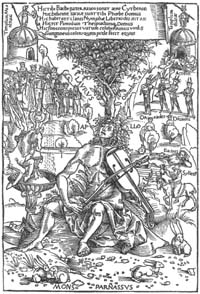

Augsburg: City of Music During the Renaissance

In the fifteenth century, the imperial city of Augsburg experienced a rise in economic and political status. The resulting desire of the leading classes to display their newfound wealth and prestige also led to a blooming of the Augsburg musical life, reflected for example in the Institution of the Augsburg City Musicians («Stadtpfeifer»). First appearing in official records in 1388, these were full-time, permanently employed musicians who played not only for official occasions like the meeting of the Imperial Diet or the reception of important visitors, but also for the private festivities of the city's leading families. Of the thirty-five Imperial Diets of the sixteenth century, twelve were held in Augsburg - each time with the participation of countless princes and their massive retinues. The Emperors Maximilian I and Charles V often stopped in Augsburg, and the court chapel of Maximilian I was resident there from 1492 to 1496. Many of its members - the organist and composer Paul Hofhaimer (1459-1537), for example - later gained the right of Augsburg citizenship. The sixteenth century saw not only the occurrence of official cultivation of music through the City Musicians, but also the beginning of musical patronage by individual families, particularly the Fugger family.

The time around 1600 constituted another high point in Augsburg's cultural history. This was true, also, of the musical life of the city, the vitality of which became apparent when, in the years 1600 and 1601, the organist and composer Hans Leo Hassler (1564-1612) was the leader of the Augsburg City Musicians. The significance of the Augsburg Musicians is also clear from the fact that many individuals among them were later taken into service at the court chapels of Munich, Stuttgart, Innsbruck, Salzburg, Ferrara, Mantua, and Florence.

With regard to ecclesiastical music, the episcopal cathedral and the Benedictine Abbey of St. Ulrich and Afra stand out on the Catholic side.

A Cathedral Choir, complete with conductor and organist, was established in 1561. The high tide of the patronisation of liturgical music, rung in with the founding of that choir, was cultivated primarily by the composer and vicar of the cathedral, Gregor Aichinger (1564-1628), who had been a student of Giovanni Gabrieli.

On the Protestant side, the choir of St. Anna, the principle Protestant church in the city, is a prominent example.

In 1581, the composer Adam Gumpelzhaimer (1559-1625) became choir master at St. Anna, and the choir performed an extensive interdenominational repertoire under his direction.

The State and City Library of Augsburg

The Augsburg City Library («Stadtbibliothek») was established in 1537. Many cloisters had been dissolved in the course of the Reformation, and so the basic components of the new library were formed from parts of the collections of the abolished mendicant orders such as the Carmelites, Dominicans, and Franciscans. The rector of the Gymnasium of St. Anna (founded in 1531) was named city librarian. In the first years of its existence, the library had an acquisitions budget of 50 Guilders per year. In 1535, 100 Greek manuscripts were purchased in Venice, and their possession brought the Augsburg Library immediate fame. Two seminary libraries with Reformation literature were also purchased. Under its learned leaders - Hieronymus Wolf, for instance, and, later, Georg Henisch - the library was developed in the sixteenth century into a research institute of some note. Following the trail blazed by the Bibliotheca Palatina from Heidelberg to Rome, the Augsburg Library became the most important Protestant library in Germany.

Up to 1618, further considerable expenditures were effected for the expansion of the library, and the Historian and city patron, Marcus Welser (d. 1614), left his 2,266 volume personal library to the city. During the Thirty Years War, however, the previously intensive pursuit of the library's development dropped back markedly. It was only slowly that it later won back a part of its earlier reputation, not to mention its financial and organizational stability. The 1677 order - coming for the first time from a Council Decree - that all Augsburg printers and publishers must deliver to the library a sample copy of every book produced, went a long way in aiding the library's return to status.

A serious setback for the library's development, however, occurred with secularisation. After the imperial city of Augsburg lost its independence in 1806 and was made a part of the Bavarian state, the library had to give all especially precious manuscripts (like the aforementioned Greek MSS), incunabuli, and early prints to the Munich Hofbibliothek. On the other hand, these losses were compensated by large gains from the spoils of secularisation.

After 1806, the library held book collections from the following ecclesiastical libraries: nearly 10,000 volumes from the Benedictine Abbey of St. Ulrich and Afra, including many music MSS; from the Augustinian canonic seminaries of St. George and Holy Cross, from the Dominican cloister, the cloister of the Franciscan observers, that of the Capuchins, and from the seminary college St. Moritz. At the same time, the libraries of the Augsburg Jesuit college of St. Salvator and of the Evangelical College, holding together approximately 10,000 volumes, were incorporated into the City Library. Later, in the years from 1817 to 1835, the contents of more libraries, including the Eichstaetter Hofbibliothek and the church libraries from Rebdorf, Irsee, Roggenburg, Ottobeuren, Ursberg, Kempten, and Mindelheim, were absorbed into the library's holdings. By 1835, the Augsburg City Library held more than 100,000 volumes.

Today, the State and City Library owns 3,637 manuscripts, 16,247 graphic leaves, and some 450,000 prints, among which are 2,798 incunabuli, 27,790 prints of the sixteenth century, and 30,884 prints of the seventeenth century.

The Early Music Prints of the Augsburg State and City Library

The collection includes 438 prints dating from the earliest years of book-printing up to the Thirty Years War: 41 works of music theory, 10 liturgical prints, 80 collected works of mostly secular and some spiritual music, as well as 307 secular and spiritual works of prominent individual Italian, German, and Dutch composers. The collection contains many unique prints, and approximately half of the collection consists of prints done in Italy, among which are numerous products of the Printer Gardano in Venice.

While there are among the MSS countless examples of cloister holdings, especially those of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Ulrich and Afra, only a few of the printed holdings originated as spoils of secularisation. Some 40 percent of the early music prints give no hint whatsoever of their origin. A further 40 percent of the prints carry a painted rendition of the Augsburg coat of arms on their bindings. These were obviously the books containing the various instrumental parts for the Augsburg City Musicians. Next to these, the Italian prints are the most numerous. The intensive direct trade relations with Venice certainly facilitated the acquisition of the newest Italian musical prints. That newly-appeared musical pieces were acquired quite quickly is demonstrated also by the dance-collections of the Brothers Hess, published in 1555 in Breslau. The binding on these collections comes from 1558, and they carry the Augsburg Council stamp of ownership from the same year.

Besides these volumes of the City Musicians and the few prints that can be proven to come from cloister collections, there are a few from St. Anna and from the private libraries of Gregor Aichinger and Marcus Welser.

Some Highlights of the Collection

Of the works of music theory, the following are to be especially noted: Hugo Spechtshart's Flores musicae, Strasbourg 1488; Martin Agricola's Musica instrumentalis deudsch, Wittenberg 1529, and his Musica figuralis deudsch, Wittenberg 1532; Nikolaus Listenius's Rudimenta musica, Wittenberg 1533; Heinrich Glarean's Musicae Epitome ex Glareani Dodecachordo, Basel 1559; and Athanasius Kircher's Musurgia universalis, Rome 1650.

Among the liturgical prints, three prints are to be found of the early Augsburg printer Erhard Ratdolt, whose products are among the best in quality of their time period: Vigiliae ac vesperae mortuorum cum officiis secundum chorum Augustensem, Augsburg 1491; Ordo processionis ac missae celebrationis ad divinum auxilium contra infideles impetrandum, Augsburg 1496; and Divo Hieronymo sacrum. Divae Annae sacrum, Augsburg 1512.

The following are especially noteworthy examples among the collected works: Liber selectarum cantionum, collected by Ludwig Senfl, Augsburg 1520; both collections of Spanish, Italian, English, and French, as well as German and Polish dances, published by the brothers Paul and Bartholomäus Hess in Breslau 1555; the collection I dolci et harmoniosi concenti, Venice 1562; and the Hortus musicalis, works of italian composers collected by Michael Herrer in Munich 1609.

Of the 307 secular and spiritual works of individual composers, the Melopoiae sive harmoniae tetracenticae of Petrus Tritonius (a setting to music of the Odes of Horace), which appeared in Augsburg in 1507, must be specially mentioned. The collection also holds a large number of works from the composers Agostino Agazzari, Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi, Jacob Hándl, Hans Leo Hassler, Fernando de la Infantas, Marc Antonio Ingegnieri, Orlando di Lasso, Luca Marenzio, Philippe de Monte, Giovanni Prioli, Jacob Regnard, and Orazio Vecchi.

The Microfiche Edition

The Augsburg Choirmaster Hans Michael Schletterer (1824-1893) had, by the 1870s, already produced a «Catalogue of the Music Works to be found in Augsburg in the Region and City Library, the City Archives, and the Library of the Historical Society». This microfiche edition is based on his 1878 catalogue, which is still valid to a great extent today. Three of the works Schletterer listed are no longer in evidence in the State and City Library, and 19 prints missing from his catalogue will be included in this edition. A CD-ROM list of all prints, based on Schletterer's catalogue, makes the edition completely accessible.