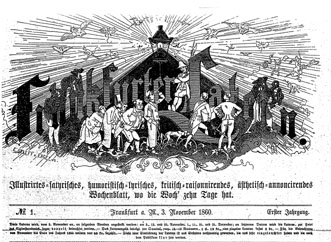

Frankfurter Latern (1860 – 1865)

Friedrich Stoltze's Frankfurter Latern (1865 – 1866)

Neue Frankfurter Leuchte (1868)

Frankfurter Latern (1870)

Deutsche Latern (1870)

Frankfurter Latern (1871)

Neue Frankfurter Latern (1871)

Frankfurter Latern (1872 – 1893)

Frankfurt am Main

together 5,671 pages on 111 microfiches

1998, ISBN 3-89131-279-2

Diazo (negative): EUR 350.–

Silver (positive): EUR 500.–

The Frankfurter Latern, which appeared between 1860 and 1893, belonged (within the genre of German political satire periodicals) to the especially sharp-tongued representatives of the «middle German» position – middle in the sense of that time as between the poles of Berlin on the one hand and Munich and Vienna on the other. Their history is full of fracture. From 1860 to 1866, they appeared regularly, each issue about four pages. After that, they appeared in a characteristic rhythm to which their oft-imitated programmatic subtitle gave clue: Illustrirtes-satyrisches, humoristisch-lyrisches, kritisch-raisonnierendes, ästehtisch-annoncierendes Wochenblatt, wo die Woch' zehn Tage hat («illustrated-satirical, humorous-lyrical, critically-reasoned, aesthetically-advertising weekly, where the week has ten days»). After that, four times a month, until the war of 1866 and the advance of the Prussians into Frankfurt obliterated them.

Responsible for the editing were the author Friedrich Stolze, a gifted satirist and upright German-patriotic democrat, and the ingenius drawer and painter Ernst Schalck, who left his unmistakable stamp on the pamphlet with his brilliant carricatures – among the best of those made in those years – until his death in 1865. His drawings drove the pamphlet through its most glorious period. From the time of Schalck's death until July of 1866, Stoltze produced the periodical alone as Friedrich Stoltze's Frankfurter Latern, now with the equally enlightening subtitle of Gasometrisch-lyrische, electrisch-satyrische, galvanisch-raisonnirische Originalbeleuchtung, alle zweihundert und vierzig Stunden herausgegeben und angezunden («gasometric-lyrical, electrically-satirical, galvanically-rational original illumination, published and lit up every two-hundred-fourty hours» – Many of these adjectives are invented).

There followed six years of prohibition, experimentation with alternatives, and evasive manoeuvre, and only a few issues: in 1867 and 1868 it was the Neue Frankfurter Latern and then the Neue Frankfurter Leuchte, a Confisziert-lyrische, arretirt-satyrische, galvanisch-raisonnierische Originalbeleuchtung, alle 768 Stunden herausgegeben und angezunden (a «confiscated-lyrical, arrested-satirical, galvanically-rational original illumination, published and lit up every 768 hours»); in 1870 it was again the Frankfurter Latern and then the Deutsche Latern, a Humoristisch-lyrisches Wochenblatt («a humorous-lyrical weekly pamphlet») in which Wilhelm Busch also took part; in 1871 again the Frankfurter Latern, and then again the Neue Frankfurter Latern. It was February 1872 before a bit of continuity became possible: A complete sequence from 1872 to 1891 followed, until Friedrich Stoltze's death. Two years later, headless, the pamphlet went under.

When the pamphlet was started, its place of publication was, like those of many other publications grounded in the tradition of the «foolish», the political carnival, and its disrespectful carnival-speech, a free city of the Holy Roman Empire, the seat of the German League, a certain centre of political happenings. By the time the pamphlet had to fold, Frankfurt am Main was merely a provincial city in the government district of Wiesbaden. This evolution also describes the history and background of the pamphlet's satires, parodies, and invectives: from «freedom» to «unity», from the great German dreams to the little German realities.

Friedrich Stoltze tolerated only illustrators as co-workers; the texts of the Frankfurter Latern were written almost exclusively by himself – at least, the most important ones – and thus the pamphlet turned out to be his life's work. Through it, he managed to churn out an astounding number of noteworthy critical achievments, especially in the early and middle years of publication. German and European politics were picked out as central themes, and international politics were also addressed – as far as it was possible to do so and remain understandable to the reader. The society and culture of the time as well as the blessings of the administrative orgies of modern statehood came under fire. Thus, for the second half of the nineteenth century, the Frankfurter Latern counted as one of the biggest, richest, and most subtle reservoirs of information.

Alfred Estermann